Source and critique relevant literature to support your proposed investigation

Samantha Sobash (2012) undertook a mixed methods research study with an aim to recognise how competition actively affects the psychological and social maturity of young dancers as people in both positive and negative ways. Her research, entitled ‘The Psychology of Competitive Dance: A Study of the Motivations for Adolescent Involvement’, is an important investigation in examining whether or not competition limits the ability to develop as well-rounded individuals or, whether it can in fact have positive impacts on self-esteem and confidence. This will provide vital information for my own investigation into the competitive world of highland dance.

Sobash conducted her research with 58 undergraduate dance students from Chapman University in California. She initially sent out a survey to garner opinions containing 64 questions. There were two versions of this survey – one for those who had experienced competition and one for those who had not, of which there were only five students. It may be necessary to conduct this particular version of the survey with more students and is something I will need to consider for my own research.

The next piece of research was a quantitative five-point likert scale asking students to rate statements such as “how much do you enjoy competing?” And “do you think dance is a competitive physical activity?” The results showed that 77.1% of the research cohort did enjoy competing, however, interestingly, only 47.9% would actively encourage other adolescents to participate in competition. 58.5% thought dance should be considered a competitive physical activity.

This idea of competition is supported by Bonnie E. Robson (2004) who wrote in her research into ‘Competition in Sport, Music and Dance’ that “competition is a social process that is so pervasive in Western Civilisation that no one can escape it.” Sobash also goes on to cite researchers, Capranica and Millard-Stafford (2011), who found that this high level of competition starts young as dancers tend to specialise at an early age in order to get to an elite level. Sobash does not agree with this process saying that:

Adolescents before puberty do not have the ability to effectively cope with

stressors associated to competition. (…) Competition is not a negative

term, but when a young individual is not physically and

psychologically mature enough to manage the situation it is

detrimental to their social development.

Other problems with competition which Sobash discusses in her paper are that, depending on the climate in which the competition arises students may worry about making mistakes which in turn impedes the learning process and ability to develop skills: “this encourages less attractive social behaviour such as personal doubt and timidity.” Participants of competition are more likely to develop a tendency to define achievement in socially comparative terms, otherwise known as ego-orientation (Robson, 2004) and Sobash’s participants gave answers on a common theme in their survey responses commenting on how they missed out on both social interactions as teenagers and on pursuing activities outside dance.

But competition is not all bad news as setting and attaining goals becomes a driving force for young competitors. Many argue this then makes dance lose the importance of gaining life skills and instilling values but this comes down to many other independent variables such as the teachers, the teaching style and the parenting. Competitive dancers also receive a high level of satisfaction from their competence (Carr and Wyon, 2003).

Ultimately, the results of this particular study are inconclusive as to whether or not competition is positive or negative but it does develop a deeper understanding of dancers’ attitudes towards competitive dance. Sobash concludes that in-depth interviews may give more conclusive evidence and therefore I will take this into consideration for my own study.

*

Competitive dance often leads to, and demands, perfectionism and it is in this area which Donna Krasnow, Lynda Mainwaring and Gretchen Kerr conduct their research.

A common theme in perfectionism theory is that perfectionists are motivated by a fear of failure, and thus, any evaluated performance is viewed as an opportunity to fail rather than to succeed. It has been suggested that perfectionistic athletes fear failure and mistakes to the extent that enjoyment of sport is greatly diminished and performance is impeded. An integral aspect of the perfectionism construct is performance standards, which is a primary focus in elite dance and sport. Therefore, examining the role perfectionism plays in elite performance seems a worthy pursuit for which little empirical research exists.

Krasnow, Mainwaring and Kerr pursued this research as part of their paper, entitled ‘Injury, Stress, and Perfectionism in Young Dancers and Gymnasts.’ They used a quantitative data gathering approach with thirty gymnasts and thirty five dancers aged 12-18 who had been training in their respective sport for ten years or more. All were female, most trained five times a week and all had significant competition experience. It is this competitive component which interests me most in relation to my own study.

The researchers used a questionnaire, a survey and a perfectionism scale to come to conclusions about whether or not their three areas were linked, and more importantly for my own research, whether there were negative impacts to excessive high standards of competition. In looking at perfectionism in particular they looked at the five primary dimensions defined by Frost, Marten, Lahart and Roseblate in 1990: personal standards, concern over mistakes, parental expectations, parental criticism and doubts about actions.

Interestingly ‘doubts about actions’ and ‘concern over mistakes’ were dependent on dance style with ballet coming out higher over modern dance on both scales and all dancers coming above gymnasts in having doubts about their actions. The results also showed that the performance and training demands on the case studies were often substantial and left young women feeling vulnerable although researchers were keen to point out that personality, environmental factors and levels of support offered could have a bearing on the results and felt that there needed to be a larger sample used with an exploration of how these things could affect the psychology of dancers (and gymnasts). Further research is also needed in order to “minimise negative effects”, something I want to look at in my small scale study.

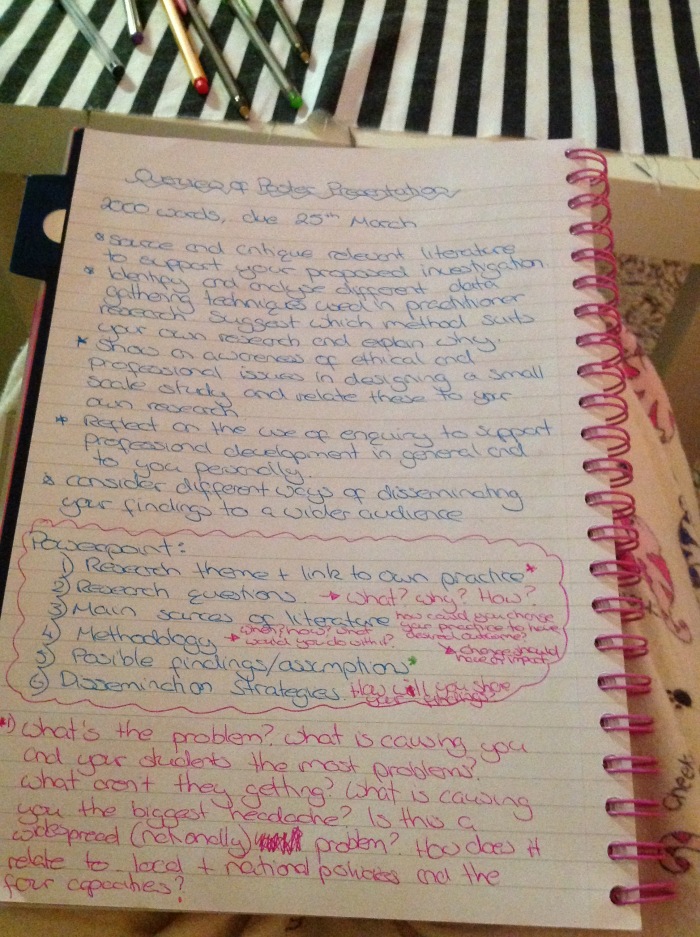

Identify and analyse different data gathering techniques used in practitioner research. Suggest which method suits your own research and explain why

Despite my literature using mixed method and quantitative research methods, based on their conclusions I will be using a qualitative approach as it is more subjective and should give me more answers to the what, the how and the why which I wish to answer. Sobash (2012) concluded that in-depth interviews may have given more conclusive evidence for her study and Krasnow, Mainwaring and Kerr (1999) noted that there were many aspects of the research area that could not be accessed by data gathering alone, such as the thoughts, feelings and perceptions of their participants.

Therefore, I will gather my data via interviews with a purposive sampling group. I have chosen this type as I need a specific set of candidates for my research with a specific set of skills, however, during my research into sampling methods it became clear that there are dangers with this method. As each sample is based entirely on the judgment of the researcher, there is a possibility of researcher bias towards the subjects and therefore the answers they give (Oppong 2013). Having clear intentions and a sound understanding of ethics should limit or negate this impact.

As well as interviews I may trial a focus group as part of my research. Dr Anita Gibbs, from Oxford University defines focus groups as research involving organised discussion with a selected group of individuals to gain information about their views and experiences of a topic. This type of interviewing is particularly suited for obtaining several perspectives about the same topic and has many benefits such as: gaining insights into people’s shared understandings of a topic, gaining many opinions at once and opening up broader views of a particular issue. Nevertheless, it is important for researchers to always be aware of the problems which may arise with their chosen research and Gibbs highlights there can be difficulties when attempting to identify the individual view from the group view in a focus group and there are practical considerations which have to be taken into account when conducting a focus group. These problems can be overcome with strong leadership and interpersonal skills.

Show an awareness of ethical and professional issues in designing a small scale study and relate these to your own research

In addition to being aware of the potential pitfalls involved in sampling and research methods researchers need to be constantly aware of how and why they are conducting the research and recognise at what points their own beliefs, opinions and prior assumptions might influence data collection or analysis. Researchers must be professional at all times, ensure they get the informed consent of all participants, ensure protection from any harm during the process, have respect for the integrity of the participants, ensure privacy, make participants aware of their right to withdraw at any time and do not get personally involved and lose objectivity. This could be potentially difficult given the nature of the sample group already being known to me as competitive highland dancers but with professional integrity at the heart of all we do as teachers I must just be aware of the potential problems with conducting a small scale study and keep them at the forefront of my mind when I am conducting my research.

When working with young people researchers could also run the risk of pupils ‘opening up’ and revealing information that as a teacher you would have to disclose but as a researcher be confidential with. Uwe Flick (2014) looks at this issue in depth in chapter four of ‘An Introduction to Qualitative Research.’ When Flick encountered this very situation during research he had to be aware that despite confidentiality agreements the information that had been disclosed might prove damaging to the participant or to others. In practice he advises: “If you sense an interview might be moving in a personal direction, you might have to stop the interview and suggest to the participant that they talk to a counsellor or other trusted support person.” He ended this section of his book with clarification of the position as researcher in these scenarios:

It is your responsibility to keep the information you learn confidential. If you sense that an individual is in an emergency situation, you might decide that you can waive your promise for the good of the individual or of others. You need to be much more sensitive to information that you obtain from minors and others who might be in a vulnerable position.

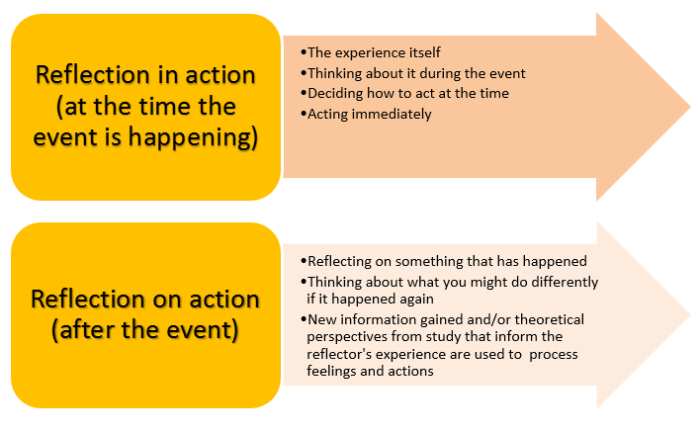

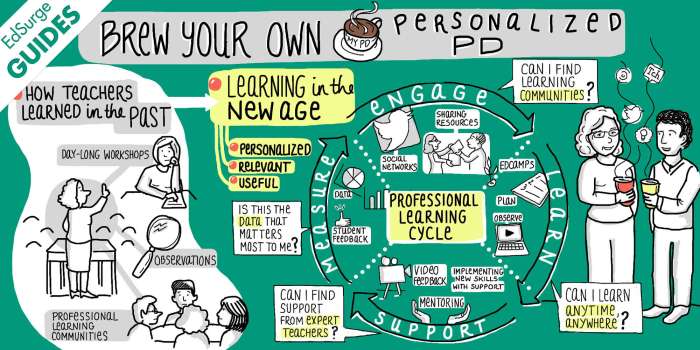

Reflect on the use of enquiry to support professional development in general and to you personally

Practitioner enquiry is essential for career progression and central to the General Teaching Council for Scotland’s new professional update which demands “professional learning”. This professional learning involves teachers being engaged in work which will stimulate their thinking and professional knowledge and ensure that their practice is critically informed and up-to-date. Furthermore, the GTCS website says that:

We believe that by undertaking a wide range of high-quality, sustained professional learning experiences, teachers are more likely to inspire pupils and provide high quality teaching and learning experiences, enabling learners to achieve their best.

On a personal level practitioner enquiry allows teachers a necessary opportunity for self-reflection of current practices and what could be improved within this current practice. Before undertaking this Masters programme I had completed a Developing Teacher Leadership course which lead to a collaborative practitioner enquiry and ultimately, the opening of the school’s Dance Academy. As I now see the benefits of this enquiry everyday I am only encouraged further to develop my practice and the research in my area of work to benefit even more young people. This particular piece of research allows me to delve deeper into my dance specialism – highland, and focus on an area of personal interest within education – health and wellbeing.

Consider different ways of disseminating your findings to a wider audience

Initially I could share my findings within my own school. I have already approached the deputy head teacher to offer sharing my practitioner enquiry practice and I think teachers would appreciate seeing a worked example of a small scale study. If this is successful I could then share it with our triad schools and with the council area schools at a joint in-service.

Furthermore, I am registered with the Scottish Dance Teachers’ Alliance who hold regular lecture series on highland dancing and it would be a great opportunity to present my findings here if the results show a need for change within competitive highland dancing.

Bibliography

Capranica, L. and Millard‐Stafford, M. L. (2011) ‘Youth Sport Specialization: How to Manage Competition and Training’ in International Journal Of Sports Physiology and Performance pp 572‐579.

Carr, S. and Wyon, M. (2003) ‘The impact of motivational climate on dance students’ achievement goals, trait anxiety, and perfectionism’ in The Journal Of Dance Medicine and Science pp 105‐114.

Flick, U. (2014) An Introduction to Qualitative Research. London: Sage Publications

Frost, R., Marten, R., Lahart, C. and Rosenblate R. (1990) ‘The dimensions of perfectionism’ in Cognitive Theory and Research pp 449-468.

General Teaching Council for Scotland. (2016) Practitioner Enquiry. [online] Available at: http://www.gtcs.org.uk/professional-update/research-practitioner-enquiry/practitioner-enquiry.aspx

[Accessed 19 February 2016]

Gibbs, A. (1997) Social Research Update, Vol. 19. Surrey: University of Surrey

Hall, F. (2008) Competitive Irish Dance: Art, Sport, Duty. Madison: Macater Press.

Hamilton, L.H., Hamilton, W.G., Meltzer, J.D., Marshall, P. and Molnar, M. (1989) ‘Personality, stress, and injuries in professional ballet dancers’ in The American Journal of Sports Medicine pp 263-267.

Krasnow, D., Mainwaring, M.S. and Kerr, G. (1999) ‘Injury, Stress and Perfectionism in Young Dancers and Gymnasts’ in Journal of Dance Medicine and Science, Vol. 3: No. 2.

Oppong, S. H. (2013). ‘The Problem of Sampling in Qualitative Research’ in Asian Journal of Management Sciences and Education, Vol. 2: No. 2.

Robson, B. E. (2004) ‘Competition in Sport, Music and Dance’ in Medical Problems of Performing Arts pp 160-166.

Sobash, S. (2012). ‘The Psychology of Competitive Dance: A Study of the Motivations for Adolescent Involvement’ in A Journal of Undergraduate Work, Vol. 3: No. 2, Article 3